The Erasmus Smith School

Erasmus Smith (1611 – 1691) was an English merchant and a landowner with possessions in England and Ireland. Having acquired significant wealth through trade and land transactions, he became a philanthropist in the sphere of education, treading a path between idealism and self-interest during a period of political and religious turbulence. Erasmus Smith was born in 1611 and baptised on 8 April of that year at Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire. He was the second son of Roger Smith and his second wife, Anna (née Goodman). The family had changed their name to Smith from Heriz (or Harris) when they inherited the manor of Edmondthorpe during the reign of Henry VII, and it was Erasmus's paternal grandfather, also called Erasmus, who had bought the manor of Husbands Bosworth in 1565.

During the period of Cromwell's rule and the subsequent Restoration, Smith manoeuvred to protect his position and to further his essentially Puritan religious stance, which he modified to suit the religious sensibilities of the new Royalist regime. He achieved this in part by creating an eponymous trust whereby some of his Irish property was used for the purpose of financing the education of children and provided scholarships for the most promising of those to continue their studies at Trinity College, Dublin. Erasmus Smith had become a "Turkey merchant". He was a Protestant and, like his father, by 1650 he was supplying foodstuffs to Oliver Cromwell's armies in the civil wars of that time. This applied in particular to military activities in Ireland, where the rebellion of 1641 was believed by him and others to have resulted in part from a failure of education in that country.

A Royal Charter was granted to the Trust in 1669. This stipulated its name to be The Governors of the Schools Founded by Erasmus Smith, Esq. and provided for a seal bearing the words "We are faithful to our Trust". By 1675, the new board of 32 trustees had around £600 per annum available to them from the landholdings; by the first quarter of the 18th century this had risen to £1100. Free schools were established in Templemore, Galway and Drogheda. Funding was also given to another school, in Dublin: the recently founded King's Hospital School benefited from the trust's interest by being provided with twenty scholarships at Trinity College and also apprenticeships. The trust also funded a lectureship in Hebrew at the College, and arrangements were in place to that any surplus funds generated were used for purposes such as clothing the poor children in the grammar schools and arranging apprenticeships.

Erasmus Smith set out strict guidelines for his schools as shown in this Report of the Governors from 1857:

Lawes and directions given by Erasmus Smith Esq., under his hand and seal for the better governing and ordering the public schools lately founded and erected by him.

For the Schools

The schools are founded as free Grammar Schools in behalf and for the benefit of the children of the tenants of the said Erasmus Smith, as also for the children of the tenants of this corporation, together with the children of the inhabitants, residing in, and about the towns and places where these Schools are erected, that is to say:-

The child or children of any tenants of the said Erasmus Smith, or to the said corporation, as also the children of any sub-tenant that is present occupier of any of the said lands or possessions. These all and each of them, if sent by their parents of friends, are to be taught free, and exempted from all salaries, and payments, in respect of their education, while they remain in any of those Schools.

the twenty poor children of the inhabitants of each of these townes, or within two miles distant where these Schooles are, or shall be erected, and to enjoy the same privileges of their education in all respects as the tenants children.

upon the death or removal of any of those twenty before mentioned, three or four of the Aldermen of Drogheda and Galway, respectively, and in Tipperary, the schoolmaster and two or three of the oldest inhabitants upon my lands there, may please to signify the names of such children to the Governors of he Schooles as are fitted in their judgement, for this charity, that the number from time to time may be made up.

Those children are to be instructed in the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, according to their respective capacities and fitted for the University, if their parents or friends desire it; others of them to write, cipher, that they may be fitted for disposement of trades or other employment.

There are further encouragements in relation to the poore children - as clothing while they remain in the Scooles, pensions for those that go to the University, and provisions also for those that are bound apprentices, some whereof are expressed in the charter all of which will be declared by the founder's appointment, when the revenue comes to be more fully stated.

For the Schoolmaster and Ushers

None are to be admitted schoolmasters of the said Schools but such as are the Protestant religion ...

The schoolmaster, and in his absence, the Usher shall publicily every morning read a chapter out of the Canonical Scripture and then pray, concluding at night also with prayer ...

The weakness of children is such that many times varieties of Chatechismes confounds their understandings, and the Lord Primate Ushers Chatechisme being specially commended to those Schooles in the Charter, the masters are diligently and constantly to chatechise them in that forme.

The peculiar political and religious conditions prevailing in Galway where the tenants on the Erasmus Smith property were Catholics were responsible for the comparatively poor attendance at the Grammar School up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Catholics of Galway seldom sent their children to the school, which was situated in High Street. In 1788 the celebrated and great philanthropist, the English reformer of Prisons, John Howard, visited this school, and stated that it was well conducted and provided with an able master, Mr. Campbell. "With this worthy master", says Howard, "I had much conversation relative to a more general and liberal mode of education in that country. Mr. Campbell testified the readiness of many of the Catholics to send their children to Protestant schools; and he is of opinion that many would be these means be brought over, were the most promising of them enabled, by moderate aids, to pursue their further education in the University". In 1813, the present Grammar School was erected in College Road at a cost of £5,700. It was opened on the 1st August 1815, under the Headmastership of the Rev. Mr. Whitley. The subjects taught were English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, composition in prose and verse, history, geography, the use of the globes, algebra, astronomy, and mathematics. The peculiar political and religious conditions prevailing in Galway where the tenants on the Erasmus Smith property were Catholics were responsible for the comparatively poor attendance at the Grammar School up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Catholics of Galway seldom sent their children to the school, which was situated in High Street. In 1788 the celebrated and great philanthropist, the English reformer of Prisons, John Howard, visited this school, and stated that it was well conducted and provided with an able master, Mr. Campbell. "With this worthy master", says Howard, "I had much conversation relative to a more general and liberal mode of education in that country. Mr. Campbell testified the readiness of many of the Catholics to send their children to Protestant schools; and he is of opinion that many would be these means be brought over, were the most promising of them enabled, by moderate aids, to pursue their further education in the University". In 1813, the present Grammar School was erected in College Road at a cost of £5,700. It was opened on the 1st August 1815, under the Headmastership of the Rev. Mr. Whitley. The subjects taught were English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, composition in prose and verse, history, geography, the use of the globes, algebra, astronomy, and mathematics.

Although Smith visited Dublin while overseeing his land purchases, he had no desire actually to live in Ireland. In 1655 – the year that his father died – he proposed that some of the profits from his Irish lands should be used to support five Protestant schools for boys. A Trust was established for this purpose in 1657, in relation to which Smith and the Grocers' Company had various powers of oversight. There were 18 trustees, the principal of whom was Henry Jones, who was soon to become Protestant Bishop of Meath. There have been various suggestions since at least the 19th century that creating the trust may not have been an altruistic act but rather one intended to curry favour and counter any possible legal challenges to holdings over which he had a tenuous claim, such as those obtained in Connaught. Well knowing that his titles and tenures were very precarious, and liable at a future period to be litigated, he very cunningly made a grant of lands for the founding and endowment of Protestant schools, and other charitable purposes, for which he [later, in 1669] obtained a Charter ... appointing the bench of bishops, the lord chancellor, the judges, the great law officers, all for the time being, governors and trustees; well knowing that if any flaw should ever appear in the patents, titles or tenures, under which he got the estates, the law officers would always protect and make the title good to his heirs.

The Trust initially encompassed 3,381 acres (1,368 ha) of his land. In keeping with his religious views, the schools were to teach their pupils "fear of God and good literature and to speak the English tongue", and both prayers and catechism (in the style of the Presbyterian Assembly of Divines) were compulsory. Those pupils who showed particular promise were to have the opportunity of taking up scholarships at Trinity College, Dublin. Erasmus Smith desired that the revenue from the estates be used for education.

The Trust charter also required 32 Governors, to include several bishops and archbishops and the Provost of Trinity College, Dublin. Their task was to use the money raised from the estates to establish five grammar schools and schools for the children of the tenants of the estates. Other ‘charitable uses’ to which the revenue was put were apprenticing children; paying salaries for various Trinity College, Dublin Professors including Oratory and Modern History, Oriental Tongues, Mathematics, Natural and Experimental Philosophy, and Physics; exhibitions and

scholarships for students at Trinity College; providing accommodation and a grant for The King’s Hospital or The Blue Coat School in Dublin; and also providing an annual grant to Christ’s Hospital, London, England.

His plans for the Trust were, however, overtaken by events. Cromwell died in 1658 and Smith's arrangements were not entirely acceptable to the new regime. The Restoration period, which began around 1660 and saw Charles II become king, was not sympathetic to the Puritan beliefs of the Cromwellian Interregnum. Nonetheless, Smith's venture was able to survive the political upheaval and change in moral tone, albeit in modified form. That it did so was largely due to his wealth and connections, but also because the educational purpose for which his lands were being used was clearly beneficial and because he engaged in many lawsuits in order to protect both his own interests and those of family and friends. Referred to by his enemies as "pious Erasmus with the golden purse", Smith came to an arrangement in 1667 which reduced the number of schools to three and required that he give £100 annually to one of Charles's favourite institutes, Christ's Hospital. The terms stipulated that although the schools were to be for the free education of children of Smith's tenants, they should each provide education on similar terms to a further 20 children from poor families, and that additional children could be schooled at a charge not to exceed two shillings His plans for the Trust were, however, overtaken by events. Cromwell died in 1658 and Smith's arrangements were not entirely acceptable to the new regime. The Restoration period, which began around 1660 and saw Charles II become king, was not sympathetic to the Puritan beliefs of the Cromwellian Interregnum. Nonetheless, Smith's venture was able to survive the political upheaval and change in moral tone, albeit in modified form. That it did so was largely due to his wealth and connections, but also because the educational purpose for which his lands were being used was clearly beneficial and because he engaged in many lawsuits in order to protect both his own interests and those of family and friends. Referred to by his enemies as "pious Erasmus with the golden purse", Smith came to an arrangement in 1667 which reduced the number of schools to three and required that he give £100 annually to one of Charles's favourite institutes, Christ's Hospital. The terms stipulated that although the schools were to be for the free education of children of Smith's tenants, they should each provide education on similar terms to a further 20 children from poor families, and that additional children could be schooled at a charge not to exceed two shillings

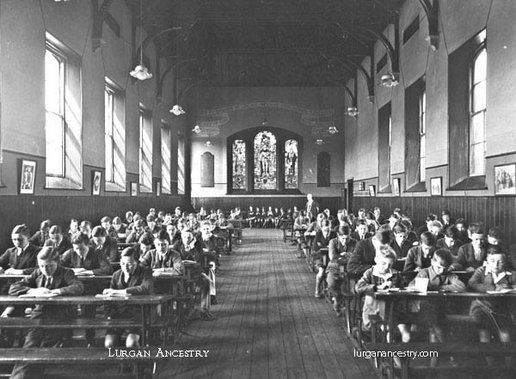

For the first half of the 19th Century, the main educational establishment in Lurgan was the Erasmus Smith School, which stood on the corner of Back Lane (now North Street) with Ulster Street. Built in 1812, it was a genuinely free school with a strong charitable connection. Thomas Warren was the first master of the School, which later became North Street National School and lasted into the 1930’s. The Back Lane School building cost £850 to build, and could accommodate 234 children. It was situated on land provided by William Brownlow, and it was officially considered to be 'the 'Parish School', with the incumbent of Shankill Parish Church paying £5 per annum towards its upkeep. The school's links with the established Church were strengthened even further by the fact that the books published by the Kildare Place Society were used in teaching. The teachers' salaries were paid by the Erasmus Smith Charity Trustees, and this would have helped to guarantee the school's independence. In 1826, the school's enrolment was 282 (158 male and 124 female)even though the school was built to accommodate 234 children. The school was genuinely mixed in religious denomination, with approx. 30% of its pupils being Roman Catholics. In 1836, when Lewis' Topographical Dictionary was being compiled, the enrolment was given as 266.

The school was supplied with two teachers (Thomas Warren and Ellen Gribben.), who each had a house and garden provided as part of the job. The 1826 report gives the salaries as £30 per annum for both teachers, although Lewis gives the figures as £20 for the master and £14 for the mistress. By 1830, the teachers had been replaced by Patrick Carroll and Ann Anderson. Mrs. Anderson was still teaching in the Erasmus Smith School in 1877 Over the same years, the mastership changed at least twice. The Directory for 1865 shows Henry Clarke as Master, while that for 1877 has Mr. R. Howell in that position. The Erasmus Smith School was a genuinely Free School, with a strong charitable connection. Poor children were clothed from the proceeds of the collection at an annual Charity Sermon, preached in the Shankill Parish Church. Heating, and other services to the school were provided by subscription from resident gentry.

For the first half of the 19th century, therefore, the Erasmus Smith School provided the bulk of the children in Lurgan with all the education they would ever receive. By the second half of the century, however, new developments, particularly in the field of National Education began to erode the dominant position of the Erasmus Smith School. It seems that the school buildings passed into the hands of the National Board, probably at some time in the 1890s, and it became the North Street National School. This school lasted into the 1930s, but had closed before the war started, since troops were, apparently, billeted in the buildings in 1939. It is significant that the School ended its life as a National School, because it was the development of the National Schools in Lurgan that saw the Erasmus Smith school decline in importance.

Our thanks to Ian Wilson for his contribution to this article.

|